Written by Tianna Rosa

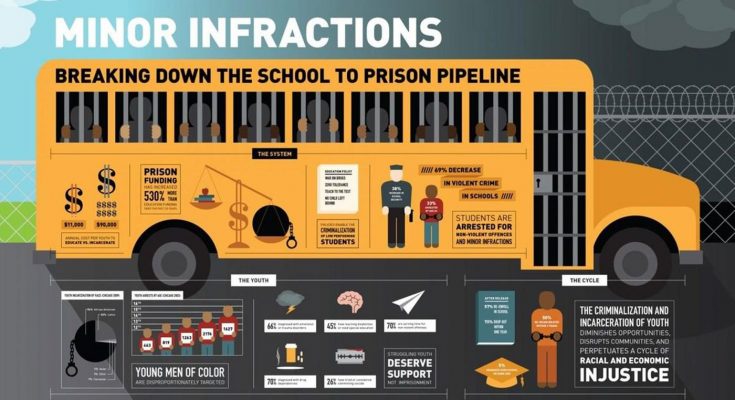

A disheartening reality for Gwinnett County Public schools are the racial disparities around school discipline. The excessive and discriminatory policies that have been put in place has disproportionately pushed students of color out of classrooms.

According to the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement K-12 Student Discipline Dashboard, 46% of all disciplinary action taken in GCPS in 2020 involved Black students, despite that Black students made up only 32% of enrolled students in the district. On the other hand, White students accounted for only 13% of disciplinary actions in 2020, despite making up 21% of the overall student population.

Punitive discipline has been such a regular occurrence, Gwinnett County has even built a courthouse on school campus. Thousands of disciplinary hearings are held each year and are conducted by numerous disciplinary hearing officers that were appointed by GCPS. The courthouse is attached to an alternative school and across the street from The Gwinnett County Department of Corrections.

Senior supervising attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Michael Tafelski said the lack of student advocacy is one of the underlying issues of the school to prison pipeline.

“When we talk about the school to prison pipeline, you can see it’s there,” Tafelski began.

“These kids get sent to these disciplinary hearings. They simultaneously get referred to juvenile court for prosecution. The majority of kids don’t have lawyers or have advocates in those hearings to defend their rights. Then they end up getting pushed out. Usually they’re found guilty, even when the evidence doesn’t support a finding. The hearing officers just kind of rubber stamp these cases. The outcome is oftentimes, in my opinion, predetermine to find these students guilty.”

Newcomer to Gwinnett County’s Board of Education, Dr. Tarece Johnson, believes discipline gaps can be better addressed with more restorative justice practices and root cause analysis.

“We’re using government funding for our academic enrichment in our kids,” Dr. Johnson said. But we’re also having a more robust social-emotional focus. We’re using the funds to be able to get more social workers and to be able to support more programs that can provide some sort of creative ways for social and emotional engagement.”

The national center of education showed in 2017-18 that about 79% of teachers in America are white women. Dr. Johnson had also confirmed that most teachers in Gwinnett are white, while most students are Black and Hispanic.

“We recognize that the data is the data,” Dr. Johnson said. “It is factual that black and brown students are disproportionately impacted in our school system. We also understand that most of our teachers are white. We have the opportunity to help them understand implicit biases and to subconsciously understand the nuanced needs of black and brown students and how the cultural differences is something to recognize and respect.”

There are several aspects that come into play when identifying the root of this problem. Reducing class sizes and focusing on the hierarchy of needs in their students will also foster a more restorative foundation according to Dr. Johnson. The polarizing debates that have emerged from pandemic—whether it be mask mandates or in-person versus digital learning—also drive this issue into new territories.

With a new superintendent on board, there seems to be hope and a promise for Gwinnett County’s academic landscape. New perspectives and programs, such as DLI and agSTEM, have been implemented for the new school year. As well as an addition of 14 new social workers.

“There’s a real opportunity to reimagine how the district has historically disciplined students,” Tafelski said. “And I’m hopeful that with new board leadership and a new superintendent, that they will take that seriously.”