The Reckoning of Morris Dees and the Southern Poverty Law Center

Looking at how the Southern Poverty Law Center comes out against pro-Black groups labeling them racist or terrorist. As the Bible says,

Or how wilt thou say to thy brother, Let me pull out themote out of thine eye; and, behold, a beam is in thine own eye?

King James Bible

Here is a New Yorker article by Bob Moser that details why the Southern Poverty Law Center is a perfect example of the hypocrisy of the United States of America. Read the full article below.

By Bob Moser for the New Yorker| March 21, 2019

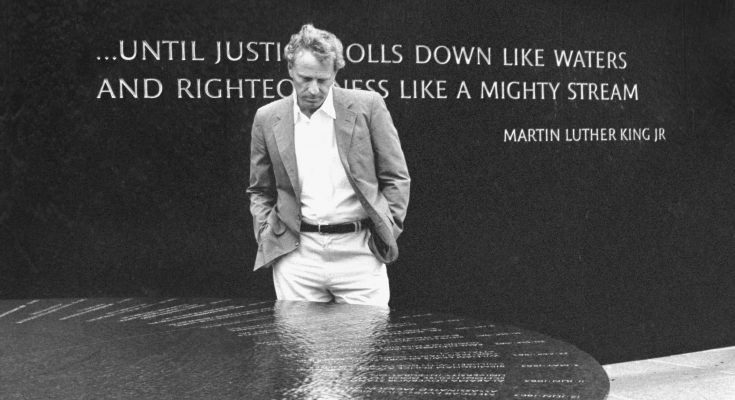

In the days since the stunning dismissal of Morris Dees, the co-founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center, on March 14th, I’ve been thinking about the jokes my S.P.L.C. colleagues and I used to tell to keep ourselves sane. Walking to lunch past the center’s Maya Lin–designed memorial to civil-rights martyrs, we’d cast a glance at the inscription from Martin Luther King, Jr., etched into the black marble—“Until justice rolls down like waters”—and intone, in our deepest voices, “Until justice rolls down like dollars.” The Law Center had a way of turning idealists into cynics; like most liberals, our view of the S.P.L.C. before we arrived had been shaped by its oft-cited listings of U.S. hate groups, its reputation for winning cases against the Ku Klux Klan and Aryan Nations, and its stream of direct-mail pleas for money to keep the good work going. The mailers, in particular, painted a vivid picture of a scrappy band of intrepid attorneys and hate-group monitors, working under constant threat of death to fight hatred and injustice in the deepest heart of Dixie. When the S.P.L.C. hired me as a writer, in 2001, I figured I knew what to expect: long hours working with humble resources and a highly diverse bunch of super-dedicated colleagues. I felt self-righteous about the work before I’d even begun it.

The first surprise was the office itself. On a hill in downtown Montgomery, down the street from both Jefferson Davis’s Confederate White House and the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where M.L.K. preached and organized, the center had recently built a massive modernist glass-and-steel structure that the social critic James Howard Kunstler would later liken to a “Darth Vader building” that made social justice “look despotic.” It was a cold place inside, too. The entrance was through an underground bunker, past multiple layers of human and electronic security. Cameras were everywhere in the open-plan office, which made me feel like a Pentagon staffer, both secure and insecure at once. But nothing was more uncomfortable than the racial dynamic that quickly became apparent: a fair number of what was then about a hundred employees were African-American, but almost all of them were administrative and support staff—“the help,” one of my black colleagues said pointedly. The “professional staff”—the lawyers, researchers, educators, public-relations officers, and fund-raisers—were almost exclusively white. Just two staffers, including me, were openly gay.

During my first few weeks, a friendly new co-worker couldn’t help laughing at my bewilderment. “Well, honey, welcome to the Poverty Palace,” she said. “I can guaran-damn-tee that you will never step foot in a more contradictory place as long as you live.”

“Everything feels so out of whack,” I said. “Where are the lawyers? Where’s the diversity? What in God’s name is going on here?”

“And you call yourself a journalist!” she said, laughing again. “Clearly you didn’t do your research.”

In the decade or so before I’d arrived, the center’s reputation as a beacon of justice had taken some hits from reporters who’d peered behind the façade. In 1995, the Montgomery Advertiser had been a Pulitzer finalist for a series that documented, among other things, staffers’ allegations of racial discrimination within the organization. In Harper’s, Ken Silverstein had revealed that the center had accumulated an endowment topping a hundred and twenty million dollars while paying lavish salaries to its highest-ranking staffers and spending far less than most nonprofit groups on the work that it claimed to do. The great Southern journalist John Egerton, writing for The Progressive, had painted a damning portrait of Dees, the center’s longtime mastermind, as a “super-salesman and master fundraiser” who viewed civil-rights work mainly as a marketing tool for bilking gullible Northern liberals. “We just run our business like a business,” Dees told Egerton. “Whether you’re selling cakes or causes, it’s all the same.”

Co-workers stealthily passed along these articles to me—it was a rite of passage for new staffers, a cautionary heads-up about what we’d stepped into with our noble intentions. Incoming female staffers were additionally warned by their new colleagues about Dees’s reputation for hitting on young women. And the unchecked power of the lavishly compensated white men at the top of the organization—Dees and the center’s president, Richard Cohen—made staffers pessimistic that any of these issues would ever be addressed. “I expected there’d be a lot of creative bickering, a sort of democratic free-for-all,” my friend Brian, a journalist who came aboard a year after me, said one day. “But everybody is so deferential to Morris and Richard. It’s like a fucking monarchy around here.” The work could be meaningful and gratifying. But it was hard, for many of us, not to feel like we’d become pawns in what was, in many respects, a highly profitable scam.

For the many former staffers who have come and gone through the center’s doors—I left in 2004—the queasy feelings came rushing back last week, when the news broke that Dees, now eighty-two, had been fired. The official statement sent by Cohen, who took control of the S.P.L.C. in 2003, didn’t specify why Dees had been dismissed, but it contained some broad hints. “We’re committed to ensuring that our workplace embodies the values we espouse—truth, justice, equity, and inclusion,” Cohen wrote. “When one of our own fails to meet those standards, no matter his or her role in the organization, we take it seriously and must take appropriate action.” Dees’s profile was immediately erased from the S.P.L.C.’s Web site—amazing, considering that he had remained, to the end, the main face and voice of the center, his signature on most of the direct-mail appeals that didn’t come from celebrity supporters, such as the author Toni Morrison.

While right-wingers tweeted gleefully about the demise of a figure they’d long vilified—“Hate group founder has been fired by his hate group,” the alt-right provocateur Mike Cernovich chirped—S.P.L.C. alums immediately reconnected with one another, buzzing about what might have happened and puzzling over the timing, sixteen years after Dees handed the reins to Cohen and went into semi-retirement. “I guess there’s nothing like a funeral to bring families back together,” another former writer at the center said, speculating about what might have prompted the move. “It could be racial, sexual, financial—that place was a virtual buffet of injustices,” she said. Why would they fire him now?

One day later, the Los Angeles Times and the Alabama Political Reporter reported that Dees’s ouster had come amid a staff revolt over the mistreatment of nonwhite and female staffers, which was sparked by the resignation of the senior attorney Meredith Horton, the highest-ranking African-American woman at the center. A number of staffers subsequently signed onto two letters of protest to the center’s leadership, alleging that multiple reports of sexual harassment by Dees through the years had been ignored or covered up, and sometimes resulted in retaliation against the women making the claims. (Dees denied the allegations, telling a reporter, “I don’t know who you’re talking to or talking about, but that is not right.”)

The staffers wrote that Dees’s firing was welcome but insufficient: their larger concern, they emphasized, was a widespread pattern of racial and gender discrimination by the center’s current leadership, stretching back many years. (The S.P.L.C. has since appointed Tina Tchen, a former chief of staff for Michelle Obama, to conduct a review of its workplace environment.) If Cohen and other senior leaders thought that they could shunt the blame, the riled-up staffers seem determined to prove them wrong. One of my former female colleagues told me that she didn’t want to go into details of her harassment for this story, because she believes the focus should be on the S.P.L.C.’s current leadership. “I just gotta hope your piece helps keep the momentum for change going,” she said. Stephen Bright, a Yale professor and longtime S.P.L.C. critic, told me, “These chickens took a very long flight before they came home to roost.” The question, for current and former staffers alike, is how many chickens will come to justice before this long-overdue reckoning is complete.

Original article can be read at https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-reckoning-of-morris-dees-and-the-southern-poverty-law-center.