BY YEMI TOURE | MARCH 3, 1991 | 12 AM PT | TIMES STAFF WRITER

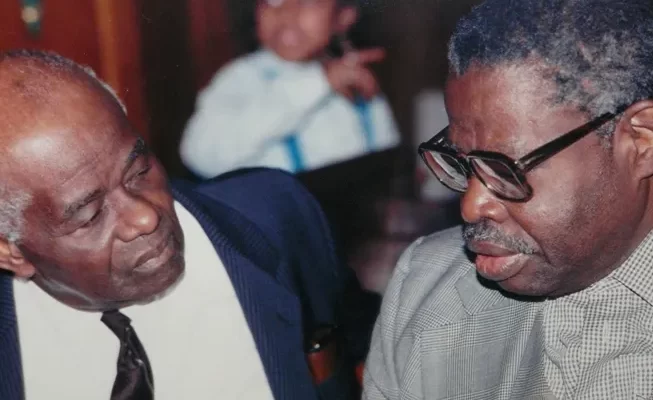

It was only 8:30 on a Friday evening at the carpeted, cozy Eso Won bookstore in South-Central Los Angeles. But the body clock of Henrik Clarke, 76, who had just flown in from New York for a book-signing party in his honor, said it was already 11:30 p.m., his normal bedtime.

And so, seated behind a table with copies of his book on Malcolm X stacked before him, his gray suit accented with an embroidered strip of the colorful Kente cloth of Ghana draped around his neck like a shawl, and admirers of his lifelong work in black history just arriving, John Henrik Clarke, teacher, historian, essayist, respected elder, closed his eyes.

The prophet at rest.

Visitors unfamiliar with Clarke’s habits might have thought he was dozing, so they talked quietly, waiting for him to stir. “He’s not sleeping,” said Isisara Bey, a longtime friend of Clarke. “Actually, he’s just waiting for a question.” He got one.

“Dr. Clarke”–he is invariably called “Dr.,” although he took only undergraduate classes at several universities in New York–“what do you think about importing water into Africa to fight the drought?”

Clarke’s eyes opened and fixed on the questioner. “There is enough water there naturally to irrigate the whole continent. There is just not enough engineering to give that water direction.”

The analyst at work.

Clarke is one of a handful of older black historians virtually unknown in the white community. But “the elders,” as they are called, are a treasure to many in the black community. They are known for rewriting history to reclaim black people’s proper place in it:

- Clarke, who lives in Harlem, has written or edited 20 books, including “Marcus Garvey and the Redemption of Africa” and “Malcolm X: The Man and His Times.” Although he is nearly blind, he is still in demand as a speaker and is working on several books.

- John G. Jackson has written “Ages of Gold and Silver,” a 331-page survey of the role of blacks in world history and religion. He started writing it in Chicago three years ago at age 80.

- Chancellor Williams, 92, lingers in a nursing home in Washington, D.C. He is author of “The Destruction of Black Civilization,” published in 1971 and still the best seller for Third World Books of Chicago, one of the largest black publishers in the United States.

- Yusef Ben-Jochannan, 72, has written 15 books, many about the black presence in ancient Egypt. Although he suffered a stroke five years ago, he has recovered and returned to New York in January from the Nubia region of Egypt, where he directs an archeological dig.

- John Hope Franklin, 76, teaches a class in constitutional law at Duke University. His “From Slavery to Freedom,” first published in 1947, is in its sixth edition and has sold 2 1/2 million copies.

Many of these historians are showered with standing ovations when they appear at university conferences. Aside from their scholarship, they regularly step off campus to motivate the black community to be concerned about its history. In that sense, they are part of the tradition of oral historians in Africa, says Eric Acree, whose master’s thesis at Cornell University is on Ben-Jochannan.

But with their advancing age, “an era in black scholarship is passing,” said Asa Hilliard, professor of urban education at Georgia State University in Atlanta.

While younger historians are beginning to make their marks, the generations-long work of the elders helped shape the 1960s and today reinvigorates a rising interest in black history.

JOHN HENRIK CLARKE

Clarke still has in his mind a powerful image of the woman who taught him in the fifth grade in 1925 in Columbus, Ga. Eveline Taylor was “as brown as a well-cooked biscuit,” he said recently, “as wrinkled as a drying prune, but a dedicated teacher.” She put a halt to his rambunctious play with other children because she saw something in him. “ ‘It’s no disgrace to be alone,’ she said, ‘It’s no disgrace to be right when everybody else thinks you are wrong. There is nothing wrong with being a thinker. . . . Your playing days are over.’ ”

With that, the teacher helped set the course of life for the student, for those words would reverberate in him when he later taught the junior Bible class at a local Baptist church. Clarke noticed that although many Bible stories “unfolded in Africa . . . I saw no African people in the printed and illustrated Sunday school lessons,” he wrote in 1985. “I began to suspect at this early age that someone had distorted the image of my people. My long search for the true history of African people the world over began.”

That search took him to libraries, museums, attics, archives and people’s recollections in Asia, the Caribbean, Europe, Latin America and Africa.

What he found was that the history of black people is worldwide. That “the first light of human consciousness and the world’s first civilizations were in Africa,” he said. That the so-called Dark Ages were dark only for Europe and that some African nations at the time were larger than any in Europe. That just as today Africa sends its children to Europe to study because that is where the best universities are, early Greece once sent its children to Africa to study because that was where the best universities were. That slavery, although devastating, was neither the beginning nor the end of black people’s impact on the world.

Clarke gathered his findings into books on such figures as the early 20th-Century mass movement leader Marcus Garvey and into articles with titles like “Africa in the Conquest of Spain” and “Harlem as Mecca and New Jerusalem,” and he contributed chapters to many books, including American Heritage’s two-volume “History of Africa.”

And in little churches and big community centers, Clarke brought his findings to life in talks to black audiences hungry for a history so long lost, stolen or strayed.

“I love the brother,” said Los Angeles resident Margaret Logan, a physical therapist who attended Clarke’s book-signing party. “He has all this knowledge to give that we need desperately. He makes you think about the greatness of African people.”

While he was teaching at Hunter College in New York and at Cornell University in the 1980s, Clarke’s lesson plans became well known for their thoroughness. They are so filled with references and details that the Schomburg Library in Harlem has asked for copies. Clarke plans to provide them, he said, “so that 50 years from now, when people have a hard time locating my grave, they won’t have a hard time locating my lessons.”

In 1986, the year of his retirement, the newest branch of the Cornell University Library–a 60-seat, 12,000-volume facility–was named the John Henrik Clarke Africana Studies Library.

In his Harlem brownstone, which he shares with Eugenia, his wife of 29 years, three floors and two basement levels are filled with books. These days, Clarke boxes up another batch of the 18,000-book collection, which he is donating to the main library at the Atlanta University complex in the Georgia capital.

“History is not everything,” Clarke once wrote, “but it is the starting point. History is a clock that people use to tell their time of day. It is a compass they use to find themselves on the map of human geography. It tells them where they are, what they are, but more importantly, what they must be.”

JOHN G. JACKSON

Jackson, 83, used to slip out of his Chicago nursing home and head for Catfish Digby’s restaurant for his beloved red beans and rice. That menu trashed the bland diet his doctors ordered, but it helped keep his spirit alive. Although the sojourns ended last April when he fell and broke his hip at the home, Jackson continued to draw together “Ages of Gold and Silver,” published late last year.

The book surveys early civilizations, ancient Egypt, Western Asia, China, the ancient Americas and what Jackson calls a “Golden Age” of African civilization from the 12th to the 16th centuries. The book cross-fertilizes the notions he raised in his earlier “Introduction to African Civilization,” “Christianity Before Christ” and “Man, God and Civilization.”

Jackson’s works concentrate on the ancient African impact on the world’s major religions, pointing out, for example, that the very notions of a day of judgment and the resurrection and a predecessor to the Ten Commandments can be found in papyrus records from Africa.

Jackson, who taught at Rutgers University and the State University of New York, sets forth a withering critique of the academic establishment.

“I’m surprised I got into the racket at all. These people have a system where there are thieves on top and victims on the bottom. And they don’t want anybody coming along saying something should be done” to correct the Europe-centered record, he said.

Unlike the other elders, Jackson never married.

Says historian Runoko Rashidi of Los Angeles, who visits Jackson in Chicago whenever he can: “He’s still very sharp. He’s a gold mine of information.”

But these days, not enough people go to the nursing home to explore his gifts. So to overcome the monotony, he will “carry on shenanigans” like fooling the nursing staff into believing he has done his exercises, says Kujichagulia Menelik III, Jackson’s friend and business manager for more than 10 years.

Jackson has long suffered some infirmities of old age, and the fall that broke his hip last April just added to his troubles. “I’ve been patched up by a bunch of doctors,” he said. “I have arthritis, asthma and diabetes. . . . I just sit around in a wheelchair all day.” No family, few visitors, no restaurant runs. “My life is finished,” Jackson said in a surprisingly bold, matter-of-fact voice. “I could die of sheer boredom.”

“He was having a bad day that day,” said Menelik, who recalled that Jackson phoned him days later to discuss the “nice talk” he had had with this reporter. “He just needs cultural therapy, more than physical.”

And don’t forget the red beans and rice.

CHANCELLOR WILLIAMS

It must be devastating for a historian to begin losing his memory.

“Chancellor Williams has a touch of Alzheimer’s,” said Jim Roberts, secretary to the 92-year-old longtime resident of Washington, whose books include “The Rebirth of African Civilization” and “The Destruction of Black Civilization.”

Williams’ care-givers at the Washington Center for the Aging say the disease disorients Williams about what he may have talked about that day and about his routine. It also means Williams may not be able to produce the other books locked in his mind.

Although earlier works highlighted both the past greatness of Africa and how it came to an end, Roberts said Williams is frustrated by “an ardent desire” to describe what African people must do now to retake their place on the world stage.

“But he does everything else,” Roberts said. “He’s as cantankerous as he wants to be. If he doesn’t want to take a bath, he doesn’t want to take a bath. “

In 1971 Williams published “Destruction” after getting his Ph.D at American University and after years of teaching at Howard University. The book, his best known, is a sweeping overview of the history of black nations, cultural ideas and movements reaching 6,000 years into the past.

Linda Rochon, 30, a legal secretary living in Los Angeles, read “Destruction” only six months ago, but its impact was profound: “I felt as if I had been awakened from a long sleep,” she said. Williams opened her eyes to Angola’s 17th-Century Queen Nzingha, who consolidated her nation and defeated Portuguese attackers throughout her 40-year reign. She was never captured, Williams writes.

“Destruction” is among the 15 books listed as “most influential” in a 1984 national poll of nearly 100 African-American writers, scholars and public figures. And in Los Angeles, Atlanta, Detroit and New York today, black bookstores list “Destruction” among their top sellers.

Williams’ bold look at blacks was matched by an equally bold critique of white academia.

“There are two widely different schools of scholarship,” he once wrote. “(Members of the) orthodox majority . . . develop their work faithfully in line with the authorities in the field, relying on them as sources of final truth. . . . The other school dares to challenge much of this authoritarian scholarship by subjecting the masters to critical analysis, raising all kinds of questions . . . and even inquiring about some fundamental presuppositions which underlie and color so much of their work.”

Rochon said that after reading the book she “felt very good about myself and very good about my people. . . . And remember: When Williams and the others were young men, it was not safe to talk like that, to dispel the darkness. . . . They were courageous.”

But now, spending many days alone in a nursing home, Chancellor Williams fights another kind of darkness.

YUSEF BEN-JOCHANNAN

The so-called Venus of Dusseldorf is a stone statue small enough to hold in your hand. It is in the shape of a woman, with large breasts and hips. It is one of the first known representations of the human form, having been carved around 25,000 to 15,000 BC, art historians say. It is housed in a museum in Vienna. Neither the word Venus nor the word Dusseldorf gives an indication that it was actually sculpted in southern Africa, as Ben-Jochannan contends, and was carried to Europe by early excavators.

“Dr. Ben,” as he is affectionately known, has been making such claims for more than a generation.

He has taught at Columbia University, Al-Azar University in Cairo, Rutgers and Vassar. He lives in New York with his wife, Gertrude, to whom he has been married for nearly 40 years. His 15 self-published books include “Black Man of the Nile” and “The African Origins of the Major Western Religions.” Books with titles like that are not likely to endear him to traditional Egyptologists or religious scholars, and neither will his latest work, “The African Called Ramses the Great,” which offers a positive assessment of the Pharaoh who reigned during the biblical Exodus.

His books are full to overflowing with his translations of hieroglyphic texts, black faces from ancient temples, coins and sculptures and his own hand-drawn maps and notes. But because some of his works show little editing, one critic said they look “thrown together.”

Such comments have not slowed Ben-Jochannan’s output or his travels. Still feisty at 72, he leads an annual pilgrimage of blacks to what he calls “the Holy Land” of Egypt, with its magnificent temples and pyramids.

One idea that Ben-Jochannan loves to talk about is one that is least accepted by the academic establishment. It centers on the origin of the founders of Egypt.

Ben-Jochannan and others say the original ancestors of the pharaohs originated deep within the heart of Africa, at the source of the Nile River near what is now Tanzania, and migrated north, following the flow of the Nile.

Frank Yurco, consulting Egyptologist for the Field Museum in Chicago, dismisses many of the ideas of these thinkers. “What they have done is react against 19th- and 20th-Century white scholars who tried to take Egypt out of Africa” by claiming its origins were in Europe or Asia, he says.

Yurco agrees with the elders that the “earliest traceable ancestors” of the pharaohs were in fact from Africa, saying “scholars are pretty much unified” these days that those Egyptians were “indigenous to the continent.”

But Yurco said scholars like Ben-Jochannan “have gone to the other pole (in claiming) that the Egyptians should be considered black Africans. . . . In saying that Egyptians are (indigenous to) Africa, they are correct,” but in saying Egyptians come from the source of the Nile, “they are incorrect.”

To some, this may sound like a tempest in a teapot. To others, it may sound like the last holdout of the white academic establishment, which for so many years has claimed a European origin for Egyptian culture. To still others, the admissions by Yurco and others may be a compliment, in that the research the elders carried out many years ago is acknowledged.

And although the Egyptologists may not be accepting his ideas, Ben-Jochannan, like the other elders, is not particularly knocking down their doors, either.

These men long ago accepted that most scholars will reject their research out of hand, or accept it only begrudgingly. So they avoided the temptations–some say entrapments–of mainline scholarship. The result is fewer research grants, lesser-known publishers, no fancy offices. But it also means seeing history without a European frame of reference.

JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN

One elder historian who fought hard most of his life to get into mainline scholarship is John Hope Franklin. His sojourn to the state archives in segregated North Carolina in 1939 proved prophetic. Franklin was told he had to sit in a small room away from the other visitors.

It was the beginning of almost an entire career of such battles in defense of black history and personal dignity, and Franklin has the scars and the victories to prove it.

Although Franklin has written more about the white South than about blacks, his “From Slavery to Freedom,” a comprehensive history of blacks in the United States, is required reading in many black studies courses around the country.

Franklin has traveled the back roads of Southern history and even dared to venture onto Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, rebutting the idea that Abraham Lincoln set slaves free with the Emancipation Proclamation, issued in 1863 in the middle of the Civil War. The document only covered slaves in the areas of the country Lincoln did not control, Franklin points out, “so technically no slaves were set free by the Emancipation Proclamation. The slaves were not set free until the 13th Amendment was ratified” after the war.

Now approaching retirement after 12 books, scores of articles and years of teaching, the Harvard Ph.D. finds diversion in the greenhouse at his Durham, N.C., home, 15 minutes by car from Duke University. “There are about a thousand orchids I have collected from many foreign countries,” he said.

One variety is named for him: Phalaenopsis John Hope Franklin.

Georgia State’s Asa Hilliard said Franklin and the other elders “represent a rupture with the habits of traditional historians by presenting information that is in the documents but is either suppressed or overlooked.”

The night after John Henrik Clarke’s evening book party in Los Angeles, the historian spoke at a large gathering at Artesian Well Faith Center in Compton.

While the audience stood and applauded after his introduction, Kassahun Checole, Clarke’s publisher, and historian Runoko Rashidi slowly guided his halting steps to the podium. One could feel the audience’s concern for the old man’s condition as he set aside his cane and grabbed the edges of the speaker’s stand to steady himself.

But when the applause died down, John Henrik Clarke spoke firmly, clearly and cogently without notes for the next hour and 39 minutes on the significance of his friend Malcolm X.

The teacher at work.

***

Note: Yemi Toure was a Black culturalist, writer and producer in Atlanta, Georgia and friend of the arts in metro-Atlanta.