By Erika D. Smith, Columnist, Los Angeles Times

Fourth of July is canceled.

Well, not really. But this year, of all years, it feels like it should be.

I’m reminded of the words of abolitionist Frederick Douglass who asked in 1852: “What to the American slave is your Fourth of July?”

He went on to answer his own question, of course: “A day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham.”

Indeed, 170 years later, with half of Congress defending an attempted coup by a former president and his racist mob and the Supreme Court stripping women of rights and threatening to do the same to others, I wonder how any American can celebrate “freedom” without thinking it a sham.

It’s only the words of another Black man, George Fatheree, that have given me pause.

But Fatheree had more, well, patriotic thoughts on the matter.

“This is the first time that a Black family has gotten land back where it was wrongfully taken under racially discriminatory means,” he told me. “I actually think the timing is poignant because we’ve never been more divided as a country as we are right now.”

Americans are losing faith in trusted democratic institutions because they aren’t acting in the public’s best interest.

A recent AP-NORC poll found that 85% of people are pessimistic about the direction of the country, including a growing number of Democrats. Meanwhile, the percentage of adults who consider themselves to be “extremely proud” to be American has hit an all-time low, according to Gallup.

It’s what Fatheree calls a “crisis of legitimacy.”

“If the government does something wrong and they acknowledge that and then don’t do anything about it,” he said, “people lose faith in government — our elected officials and our institutions.”

Reparations, by the most basic definition, is government acknowledging it did something wrong and then doing something about it. And that is the truest form of patriotism. A love not just of country but of the people who inhabit it.

“We’re in desperate need of healing,” Fatheree said. “And in my mind, it’s through these types of acknowledgments of injustice — and attempts to address it — that we create a foundation for healing.”

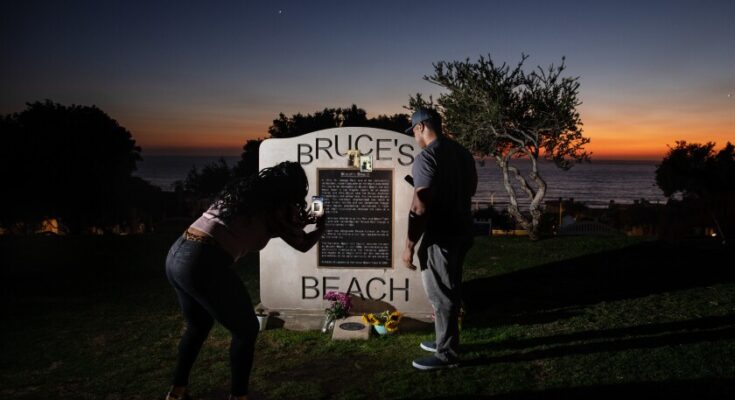

Bruce’s Beach is just one example.

Of course, not everyone agrees that we need to celebrate this sort of patriotism on the Fourth of July — or any other day of the year, for that matter. Even as calls for reparations have grown louder, polling shows most Americans generally remain opposed, especially when it comes to financial payments to compensate for slavery.

This presents a particular challenge in California.

Since last year, a nine-member task force has been meeting to hammer out an ambitious plan for reparations that the state Legislature will be asked to approve as early as next year.

In preparation, the members put out a 492-page report last month detailing the many ways that often intentionally and sometimes unintentionally racist federal, state and corporate policies have punished Black people for centuries.

Most of the information is based on research provided by dozens of experts who testified before the task force in recent months. (Not, I should note, on conspiracy theories cooked up by opportunistic crackpots who claim our government committed a wrong by “stealing” the 2020 election from former President Trump.)

Also included in the report are preliminary recommendations for reparations, such as eliminating college tuition and ending work requirements for inmates for the descendants of slaves, as well as repealing Article 34, which requires voters to OK public housing projects.

Persuading lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom to agree to any of this — much less remedies that are more radical — will almost certainly hinge on whether the task force can drum up enough public support.

Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles) alluded to this during a recent Zoom call on reparations organized by the California Democratic Party.

“The most powerful message that can come to the Legislature — and, hopefully, to the governor to sign — is that we’re united and moving forward with reparations,” he said. “Because I will be honest with you. Not everyone in the Legislature is 100% behind what we’re doing.”

To that end, the task force and its allies have been holding listening sessions, gathering input from Black Californians on what they would like to see included in a plan for reparations.

The suggestions so far have been aspirational but far from cohesive in terms of priorities.

“I don’t think we’re going to come away with a decision that’s going to make everybody happy,” state Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) said after a session in Leimert Park on Juneteenth. “But I think it’s a start. And, as you can see, it’s still a lot to be fleshed out.”

Meanwhile, promoting the task force also has been a challenge. It’s hard to get public input when the public doesn’t know you exist or have a meeting scheduled.

This is where the now famous story of Bruce’s Beach comes in. So many people are so fascinated by what has happened there that they’ve become interested in the broader push for reparations in California.

Fatheree just hopes people don’t get hung up, thinking Bruce’s Beach is the only model for what’s possible.

“Since I’ve gotten involved in taking this case, I get an email or a voicemail every day,” he told me. “They say, ‘My grandmother owned land in Texas and they took it via eminent domain.’ Or a lot of times, it’s not eminent domain. They showed up with dogs and shotguns and just took it and forged the paperwork.”

So what happened to the Bruce family isn’t at all unusual in American history. But the specific details made it an ideal case to be a landmark for reparations, Fatheree said.

It was in 1912 that the Bruces bought two lots in Manhattan Beach and opened a lodge and dance hall for Black beachgoers. It became so popular that, soon, more Black families moved in, drawing the attention of the Ku Klux Klan.

When harassment didn’t work, city officials condemned the neighborhood and seized more than two dozen properties, including the lots owned by the Bruces, supposedly to build a public park. But the land sat empty for decades.

Over time, the land passed to the state and then to the county, where it now operates a lifeguard facility. Land owned by the other families is now a park overlooking the Pacific.

“We never will know the opportunities that the Bruce family would have had if the city of Manhattan Beach had not like ripped out this tree prematurely from the roots,” Fatheree said. “And it’s not just the Bruce family. It’s the people that would have been employed at Bruce’s Beach, the people who would have gone there as children and been inspired and met other people. The jobs that would have been created. We can’t size up the opportunity that was lost.”

The idea that Black Americans will somehow be made whole with a check or a program after hundreds of years of government-induced harm is far-fetched at best. But that’s not really the point of reparations.

What matters is that an honest and humble attempt is made toward true atonement for everything from decades of housing discrimination to a criminal justice system steeped in systemic racism. And there are many ways to go about doing that, not just returning stolen land.

“There’s lots of good models and ideas out there,” Fatheree said. “What we need is the type of political leadership and courage, frankly, we’ve seen with the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to move forward and implement them.”

It’s not quite enough to make me proud to be an American this Fourth of July or think it any less of a sham. But, to echo Fatheree, it’s a start.

Erika D. Smith is a columnist for the Los Angeles Times writing about the diversity of people and places across California. She joined The Times in 2018 as an assistant editor and helped expand coverage of the state’s housing and homelessness crisis. She previously worked at the Sacramento Bee, where she was a columnist and editorial board member covering housing, homelessness and social justice issues. Before the Bee, Smith wrote for the Indianapolis Star and Akron Beacon Journal. She is a recipient of the Sigma Delta Chi award for column writing, a graduate of Ohio University and a native of the long-suffering sports town of Cleveland.