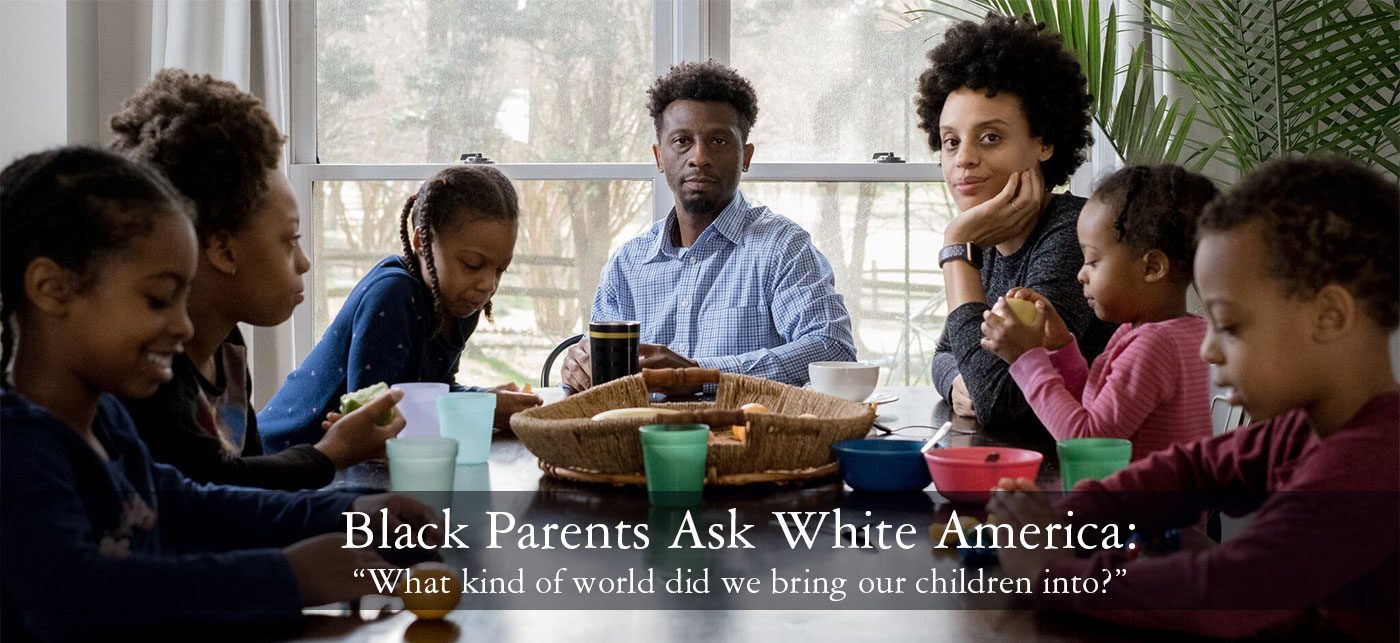

Article Photo by Eric Koch — Langston Hughes’ Broadway adaptation of ‘Black Nativity’ in 1962.

Langston Hughes’ Broadway adaptation of ‘Black Nativity’ in 1962. The birth of a child is typically a cause for celebration. It is a time of great joy and anticipation. In the case of the biblical Christ-child, the birth of the Baby Jesus was met with uncertainty, fear, and hope. […]

The birth of a child is typically a cause for celebration. It is a time of great joy and anticipation. In the case of the biblical Christ-child, the birth of the Baby Jesus was met with uncertainty, fear, and hope. Uncertainty because a virgin was to give birth to a son whom Mary was told would save the world. Fear, because the notion of a virgin giving birth was incredulous and more likely the result of pre-marital sex, an act punishable by death. Also, the arrival of this Savior posed a threat to the political leaders of the day. Yet, the anticipation of the salvation and joy this baby would bring to the world was also a cause for hope.

I’m sure the advent of Christmas was accompanied by excitement and anticipation in the households of Christian slave owners on plantations in the antebellum south. Whether or not some of that excitement rubbed off on the enslaved, they would have understood about the joy of a newborn baby.

According to the New Testament, Jesus had followers who believed he was the Messiah and that his birth promised deliverance from the rule of Rome. As with many stories from the Bible, the enslaved community was inspired by the scriptural application to their situation. Jesus was seen as a king who would not only deliver Israel, but could deliver them, too. Therefore, the arrival of Jesus into the world could be cause for celebration for the enslaved, as well.

So now let’s consider the spiritual, Mary Had a Baby. And what it could mean for African Americans today.

What if the birth of Jesus was contextualized, and Mary, Mother of God, was Black? And that Jesus was Black. That gives new meaning and relevance to the story and the song. Love, joy, peace, and hope are coming for me, are available to me, too. I can then situate myself in the story as a Black person and have access to the promise that the arrival of Jesus brings.

There are two melodies for this spiritual that I am familiar with. One is in the James Weldon Johnson & J. Rosamond Johnson collection of spirituals. This version is upbeat, and I could see it being sung as the shepherds were told of the birth of Baby Jesus by an angel and went to see for themselves. It also has connotations of freedom.

Mary had a baby,

Yes, Lord,

Mary had a baby,

Yes, my Lord,Mary had a baby,

Yes, Lord!

De people keep-a comin’ an’ de train done gone.

The train represents a vehicle, a mode of transportation; a conveyance that transports one from one place to another. In this case, from slavery to freedom. Conveyances such as trains, chariots, or even ships often represented the underground railroad and the opportunity for escape. In the biblical story of the birth of Jesus there is no train. The insertion of a train to the song is an ingenious device of the enslaved. The train often refers to “Gospel Train,” the train to heaven. During slavery times, while the slave master was caught up in celebration of the Christmas season, the distraction may have allowed those wishing to escape an easier time to get away.

The other melody is the 1947 arrangement by William Dawson of the Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University. This one doesn’t mention the train and is more serene. I can imagine this version being sung at the manger.

Mary had a baby, my Lord.

Mary had a baby, my Lord.

Oh, Mary had a baby, Mary had a baby,

Mary had a baby, my Lord.

Where was he born? Born in a manger.

What did they call him? King Jesus.

There are no allusions to freedom in this version, just reference to the biblical text and a celebration to welcome the Christ-Child. Both versions convey the story, and both allow functionality for the enslaved community. One version may facilitate freedom and another, especially through today’s lens, allow the opportunity to situate oneself in the story and connect to the joy of new birth more intimately.

Click here to view original web page at www.cpr.org

M. Roger Holland, II is Teaching Assistant Professor of African American Music and Theology at the University of Denver’s Lamont School of Music, and Director of DU’s Spirituals Project Choir.

Listen to Professor Holland’s monthly musical selections and commentary throughout the year on CPR Classical, including Sunday mornings on our choral music show Sing!, hosted by David Ginder.