by Vann Newkirk

I remember the year I tried to boycott Thanksgiving. I was 19, entering that necessary but annoying phase of young self-righteous and half-informed quasi-pro-Blackness. I drove home anyway because students were essentially kicked out of dorms for the holiday. As soon as I hit the door, the aroma of greens, fatback and yams hit me in the face like a Tyson hook. My grandmother (whom I had tipped off about my plan on the phone earlier) turned to me while stirring the greens slyly.

“You gon’ eat, or what?”

I’d never tasted greens that good before.

Let’s get this out of the way: To celebrate Thanksgiving requires a bit of contortion from those of us who try to be socially conscious. The image of Pilgrims eating peacefully with American Indians at a shared harvest feast presents a faulty view of the founding of this country — one typically framed as though there was a willing handoff between native and white. This obscures the history of violence and oppression, and it also manages to both legitimize and whitewash our country’s terrible actions toward its indigenous people.

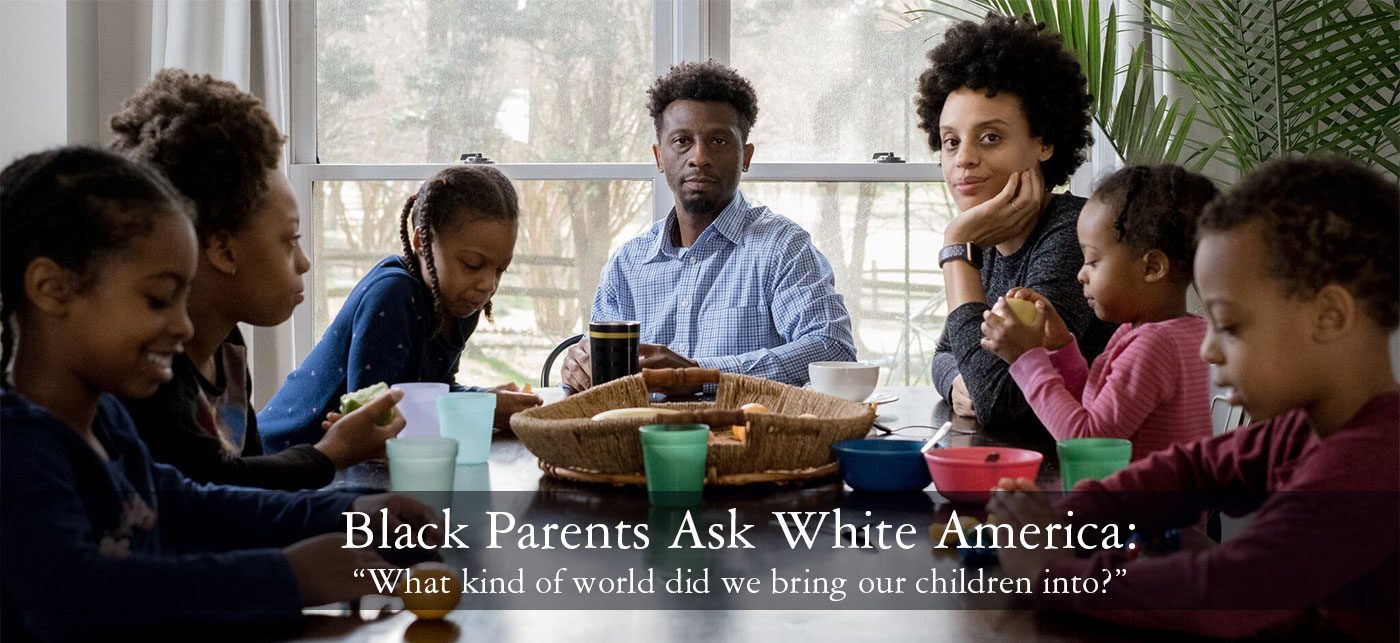

As a Black American who works every day to hold our country accountable for its rampant racial inequality that is a continuum of centuries of racism, terrorism and genocide, Thanksgiving is truly a tough holiday to process.

The love that Black people have for the Thanksgiving holiday would seem to fly in the face of our shared history with American Indians, which is defined greatly by oppression at the hands of the White majority. The holiday’s special place in the Black familial and religious tradition, however, is full of the same contradictions of pain and joy, stark awareness and carefree celebration as are all our traditions.

This is an Ebony Magazine reprint from November 26, 2019 and the question still remains. Should the Black community celebrate Thanksgiving? Please send your comments to us.