Despite being denounced by the sports press in 1968, he has emerged as a hero.

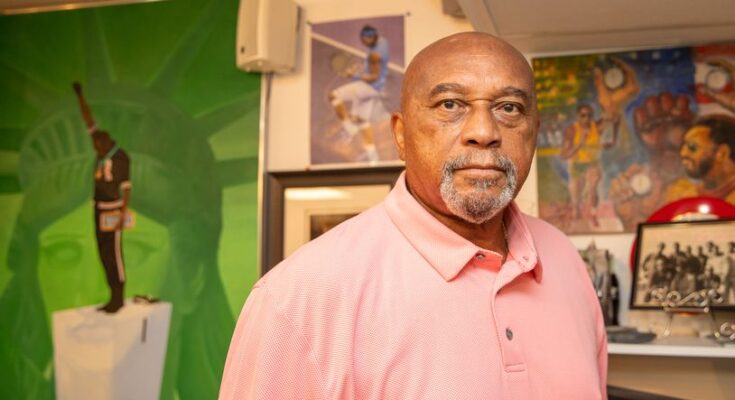

“This is my world record wall,” said Tommie Smith, 78, navigating his 6-foot-4 frame through a memorabilia-packed man cave at his Stone Mountain home.

Among these framed images we see the lanky Smith breasting the tape in the 200-meter and 400-meter races, blazing a straightaway 200, contributing to the 4×400 relay, throwing his hands in the air, triumphant and ecstatic. (”Look at those skinny legs!” he said of one photo, amused at his college kid physique.)

In one year, 1966 to 1967, Smith set 10 world records. But the one record that stands out in popular memory was the 11th, established the following year in Mexico City at the 1968 Olympics.

In his new graphic memoir, “Victory. Stand! Raising My Fist For Justice,” Smith describes his thoughts in the instant before the starting gun, as he crouched in the blocks at the Estadio Olímpico Universitario.

“Everything went silent at that moment,” he writes. “The only things on my mind were my forward momentum, winning in less than 20 seconds, and whether I had enough strength and speed to outrun a hail of bullets.”

Outrunning bullets sounds like an overstatement. But Smith and his teammate John Carlos had been receiving death threats since they first started planning a protest at the Olympics.

Those threats accelerated when Newsweek put his image on the front of the July 15, 1968, issue with the cover-line, “The Angry Black Athlete.”

“They had killed a hundred kids the week before,” Smith said, referring to the unarmed Mexico City protesters killed by soldiers during street demonstrations before the Games. Security at the Games — “There was none!” — did nothing to reassure him.

The bullets never never came to chase him. But, after Smith and Carlos raised their black-gloved fists in the Black power salute, while standing on the winner’s podium during the national anthem, other punishment landed hard.

Smith and Carlos were booed from the stadium (though there were some cheers), removed from the team and blocked from competing for life. Smith was sent home to California, where he was fired from his job.

The negative reaction from white America was thunderous, beyond anything experienced by Colin Kaepernick, the NFL player criticized for protesting during the national anthem.

This made it all the more surprising for children’s book author Derrick Barnes, when he met Smith several years ago, as the two prepared to collaborate on Smith’s story.

You would think Smith would be bitter, said Barnes. He isn’t.

Smith, he said, is a model of zen-type peaceful energy. “There’s some selflessness that happens when you stand up for others,” said Barnes. “You have to be selfless, not think about the consequences, and that’s what 24-year-old Tommie Smith did.”

In fact, as he looks around the incredible memories in this basement, Smith is delighted by one keepsake after another. Collected down here are the starting blocks from his world-record straightaway run. A gold-painted replica of his arm, made by artist Glen Kaino. A photo with famous sports broadcaster Howard Cosell, who asked him, after his Mexico City protest, “Are you proud to be an American?”

“I’m proud to be a Black American,” Smith responded.

The graphic memoir, geared for young readers, is illustrated with dramatic black-and-white drawings by Atlanta artist Dawud Anyabwile. It begins on a tenant farm in tiny Acworth, Texas, population 20.

We see Tommie, the seventh child in a family of 12 children, running to catch his older sister Sally on the way to the fishing hole, or trying to keep up with her during days picking cotton.

He credits racing with Sally, and the grinding physical labor of working the farm, for helping him develop an athlete’s physique.

Track took him to San Jose State College, and to the tutelage of Coach Bud Winter. Winter earned his school the nickname Speed City, nurturing a remarkable group of sprinters.

Three San Jose State track stars would go to the 1968 Olympics, including Smith, Carlos, and Lee Evans, a record-holder in the 400-meter.

Black athletes at the school also initiated the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which threatened a boycott of the Games in pursuit of certain goals, including the hiring of more Black coaches and a ban on South African teams at the Games.

When some of their demands were met, the protesters at San Jose decided it would be up to the individual athletes to choose their own form of protest.

John Carlos and Tommie Smith knew they might both mount the winner’s podium together, and they planned their movements, sharing a pair of black gloves: Smith wore the right glove, Carlos the left.

Enduring the harsh response, Smith had moments of doubt and depression. But he got a coaching job at Oberlin College and then at Santa Monica College, back in California, where he coached for 27 years.

In the year 2000 he married his third wife, Delois Jordan, who has served as his manager, organizing speaking engagements and marketing deals.

They moved to Atlanta in 2004. He noticed in the 1990s that attitudes toward his protest shifted. “I was no longer a pariah,” he writes. San Jose State built a 20-foot statue honoring him and John Carlos. The pair were invited to the White House by President Barack Obama in 2016.

“It was easy to illustrate,” said Anyabwile, “because it was a story of triumph.”

Through the Tommie Smith “Live the Legacy” Award, he helps inner city kids develop discipline through track and field.

When he thinks about that moment in Mexico City now, he sees it as part of a destiny ordained by a higher power.

“I only know that God created me and God had a plan for me.”