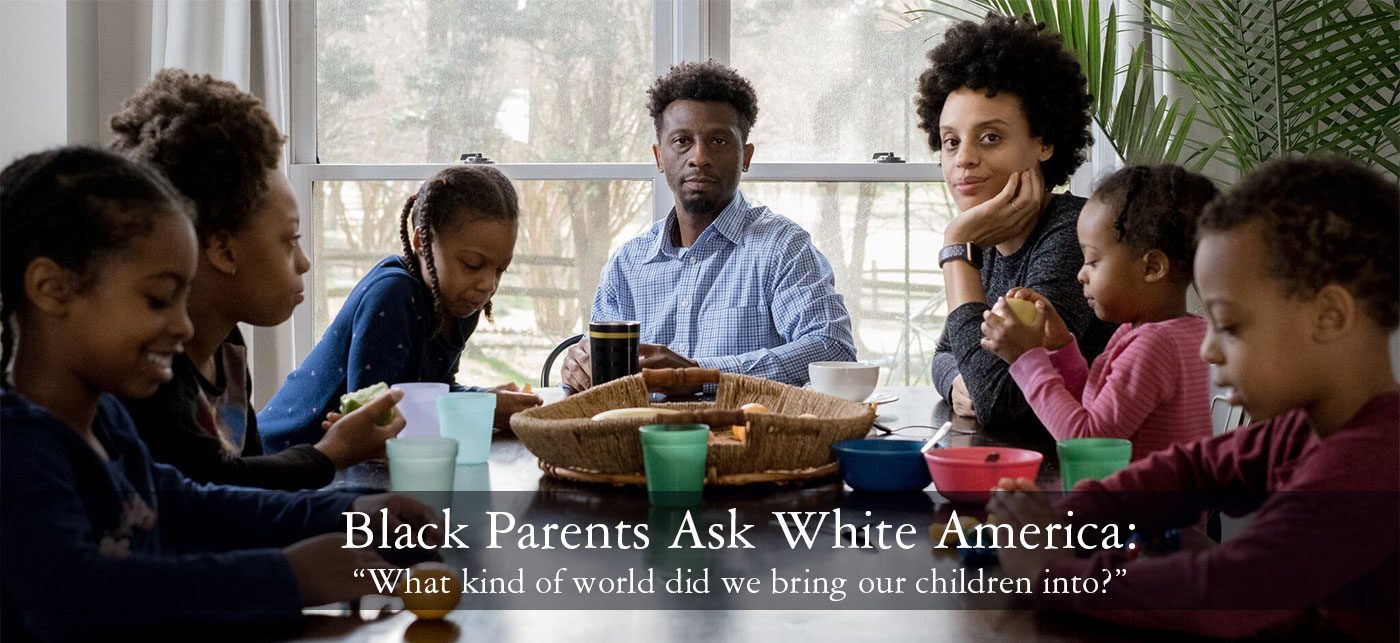

After the Supreme Court’s decision, we must urgently refocus on an agenda for equitable restitution addressing slavery and Jim Crow’s economic toll.

by Roger House

Affirmative action was a promise to deliver economic justice to Black America that fell short. It was envisioned as an array of “helping hand” policies for the descendants of enslaved people designed by the authorities that had enslaved them. It offered a slow walk to restitution based on fair access to schools, loans, jobs, and housing.

The Supreme Court decision on college admissions upends the promise. By a vote of 6 to 3, the court rejected the programs at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina as unlawful.

The decision involves the admissions processes at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina, the flagship institutions of private and public education. The cases share a common petitioner: Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), a group whose members believe that the consideration of race in college admissions — even to correct historical wrongs of racism — is unconstitutional.

Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, agreed that the “admissions programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points.”

The decision returns Black America to a crossroads of restitution for the wrongs of slavery and Jim Crow. Since the decades after the Civil War, the challenge has been to find pathways to economic justice. One strategy has looked to individual and class-action claims for reparations, another to the promise of affirmative action and inclusion.

The Shrinking of Affirmative Action

Since the 1930s, Black leadership has embraced government and company employment tools to break down historic barriers of race. Such policies worked to open doors in government offices, defense factories, and the armed services during World War II and afterward. By the 1960s, civil rights leaders expressed confidence that “affirmative action” policies could deliver a measure of economic justice.

From the start, however, the reliance on administrative tools as a primary means of restitution was stifled by persistent legal challenges, political opposition, and negative court decisions. Critics have promoted the alternative policy of a “colorblind” approach—though it has failed to address the historic and systemic inequities.

The Supreme Court decision on the Harvard and UNC admissions programs will affect the way students apply to colleges and universities and, ultimately, the number of Black students enrolled in the schools with the most resources.

The Quest for Reparations

Since the Civil War, Black Americans have initiated claims for restitution for the unjust enrichment from slavery. Understand that more than 90% of Black Americans are related to the original 400,000 Africans brought to America as commodities of labor. The pool grew to more than 4 million by the Civil War, and their bodies made America great.

America became an economic powerhouse from the institution of slavery, according to authors Sven Beckert and Seth Rockman in “Slavery’s Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development.” Africans were the primary assets of national wealth as commodities for work, sale, rent, and childbirth. They helped to build the industries of agriculture, shipping, manufacturing, railroads, publishing, finance, and insurance.

In addition to slavery, people have initiated claims for restitution for the unjust enrichment from Jim Crow, the laws and practices of racial subjugation. The loss of wages, farmland, family wealth, and markets for business stretched nearly a century and even excluded Black workers from transformational government programs like Social Security.

Among the notable claims for restitution in recent years was the 2002 lawsuit by attorney Deadria Farmer-Paellman. She filed a class action in federal court against financial institutions with ties to slavery. The claim received a degree of validation in the proceedings.

Attorney Patricia Muhammad explored appeals to the International Criminal Court in the book, “The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade: A Forgotten Crime against Humanity as Defined by International Law.” In 2019, the United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights concluded that the U.S. was among the states that owe reparations to the descendants of enslaved people.

In recent years, private actors have tried to find ways to wrest back stolen wealth, as documented by Ta-Nehisi Coates in his famous essay for The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations.” Family claims have been made to recover the value of lost farmland, business, and homes. State and local institutions have also explored pathways to restitution, such as a California task force on reparations.

The Days Ahead

As the dust from the Supreme Court decision settles, Black political leaders would be prudent to explore a new agenda of restitution for the unjust enrichment from slavery and Jim Crow.

Any agenda should encourage reliable structures for filing claims. And it should prioritize the distribution of awards in the areas of pensions, workforce development, affordable housing, debt relief, health insurance, and youth recovery.

The agenda should also seek new ways to gain access to the resources — educational, employment, and contracting — to the upper-tier schools, most of which were enriched under slavery and Jim Crow. One approach is the reparation initiative by students at Georgetown University.

To be clear, the Black community will gain more from an agenda that directs investments to HBCUs and programs at community colleges and urban public colleges that serve large numbers of their students.

Beyond the question of financial wholeness, the demand for reparations for slavery and Jim Crow has cultural merit as well. Randall Robinson, in “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” argued that the demands for reparations have roots in the dignity of Black America.

Roger House is associate professor of American Studies at Emerson College and the author of “Blue Smoke: The Recorded Journey of Big Bill Broonzy” and “South End Shout: Boston’s Forgotten Music Scene in the Jazz Age.” A version of this commentary first appeared in The Daily Beast.