This is a reprint written by Defender News Service.

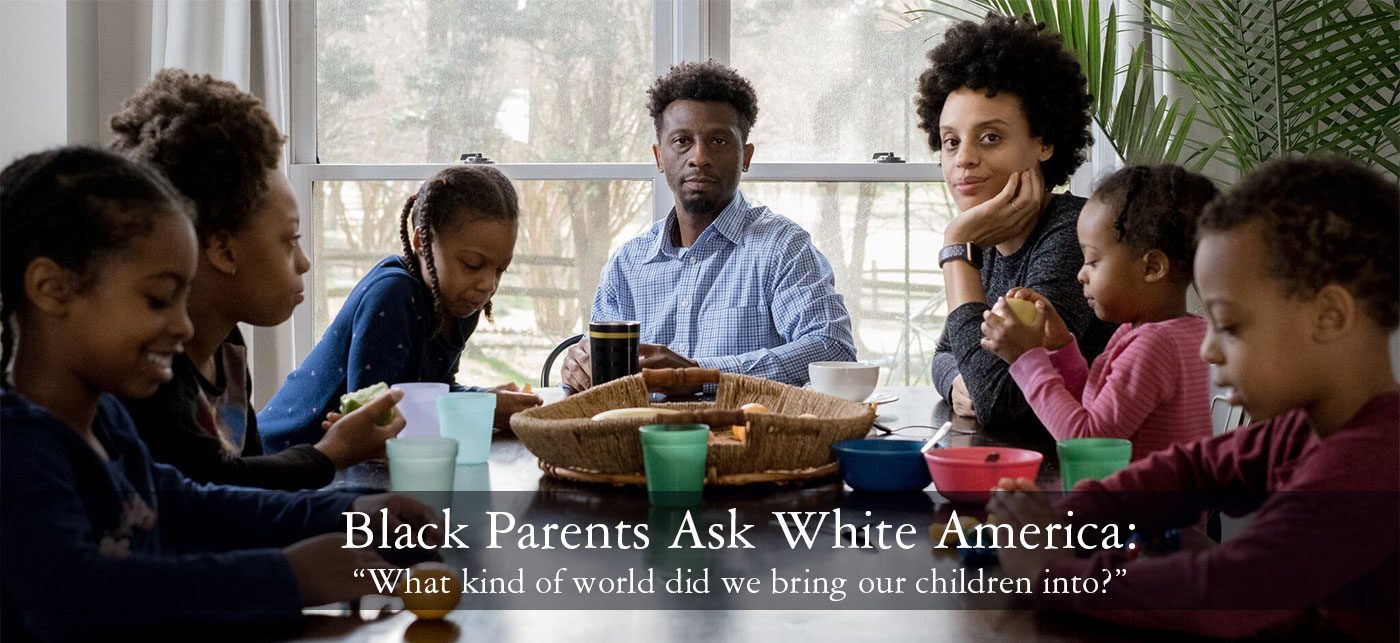

The myths of the Black father have been perpetuated for years. Various studies and reports have repeatedly told us that Black fathers are overwhelmingly absent from their children’s lives.

However, while these numbers are nothing to ignore, they contribute to a damaging narrative about Black men and negate the achievements of the number of Black men who play an active role in their children’s lives.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published new data on the role that African-American fathers play in parenting their children. The study actually defies stereotypes about Black fatherhood, finding that Black dads are more involved with their kids on a daily basis than dads from other racial groups.

In honor of Father’s Day, here are seven lies we should stop telling about Black fatherhood.

- Black Fathers aren’t involved in their children’s lives

The Pew Research Center has found similar evidence that Black dads don’t differ from white dads in any significant way, and that there isn’t the expected disparity found in so many other reports. Although Black fathers are more likely to live in separate households, Pew estimates that 67 percent of Black dads who don’t live with their kids see them at least once a month, compared to 59 percent of white dads and just 32 percent of Hispanic dads.

- Black men don’t value parenting

There’s compelling evidence that the number of Black fathers living apart from their kids stems from structural systems of inequality and poverty, not the unfounded assumption that African-American men somehow place less value on parenting. An equal numbers of Black dads and white dads tend to agree that it’s important to be a father who provides emotional support, discipline, and moral guidance. There’s one area of divergence in the way the two groups approach their parental responsibilities: Black dads are even more likely to think it’s important to financially provide for their children.

“Even though Black dads may be less likely to marry their kids’ mothers, they typically remain involved in raising their children,” said Dr. Roberta L. Coles, a sociology professor at Marquette University, who has researched Black fathers for nearly a decade.

- The lack of a father won’t end Black woes

Growing up, most of us heard the familiar refrain – most of the Black community problems would be solved if fathers simply stuck around. While that fact can’t be negated, author, Mychal Denzel Smith argues that responsible fatherhood only goes so far in a world plagued by institutionalized oppression.

“For Black children, the presence of fathers would not alter racist drug laws, prosecutorial protection of police officers who kill, mass school closures or the poisoning of their water. By focusing on the supposed absence of Black fathers, we allow ourselves to pretend this oppression is not real, while also further scapegoating black men for America’s societal ills,” Smith, author of The Invisible Man, says.

Smith believes the damage isn’t done by the absence of a father but from the feeling of abandonment.

“If Black children were raised in an environment that focused not on bemoaning their lack of fathers but on filling their lives with the nurturing love we all need to thrive, what difference would an absent father make? If they woke up in homes where electricity, running water and food were never scarce, went to schools with teachers and counselors who provided everything they needed to learn, then went home to caretakers of any gender who weren’t too exhausted to sit and talk and do homework with them, and no one ever said their lives were incomplete because they didn’t have a father, would they hold on to the pain of lack well into adulthood? This isn’t an argument in favor of deadbeat fathers, but a call to detach ourselves from the myth that the only and best way to raise a child depends on the presence of a man we call a father.”

- Single-parent households are exclusively a Black problem

The increase in number of single-parent homes has repeatedly been painted as a problem exclusively rooted in the Black community. However, that fact couldn’t be further from the truth. The number of single-parent American households has tripled in number since 1960, and while an overwhelming majority of these households are likely to be led by Black or Hispanic women, the number of Black, single-father households is also on the rise.

- Unwed mothers signal a morality problem in the Black community

According to a 2016 study, 72 percent of Black children are born to unwed mothers, a sharp contrast to the 24 percent detailed in the 1965 Moynihan Report. Some have taken this number and cited it as a contributing factor to a large portion of Black America’s present-day plight. However, many have taken issue with how this statistic has been used with respect to the Black community’s moral standing. Ta-Nehisi Coates broke down the numbers in an effort to give a more accurate depiction. “While the number of unmarried Black women has substantially grown, the actual birthrate (measured by births per 1000) for Black women is it the lowest point that its ever documented.,” he said.

So while a larger number of black women are choosing not to marry, many of those women are also choosing not to bring kids into the world. But there is something else.

“At one point married Black women were having more kids than married white women, they are now having less,” Coates added. “This dispels the idea that, somehow, the Black community has fallen into a morass of cultural pathology is convenient nostalgia. There is nothing “immoral” or “pathological” about deciding not to marry.”

- Fatherless men won’t make good fathers

There’s no disputing the effect fatherlessness has on children’s lives. Children in father-absent homes are almost four times more likely to be poor, and being raised without a father raises the risk of teen pregnancy, marrying with less than a high school degree, and forming a marriage where both partners have less than a high school degree. However, men who didn’t grow up with their fathers are not incapable of being good fathers themselves — an assumption disproportionately assigned to Black men who are more likely to be raised by single mothers.